By Ambassador of Japan to Viet Nam, Takio Yamada

Introduction

This year, Japan and Viet Nam are celebrating the 50th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between the two. Today’s Japan-Viet Nam relations are at their best ever in all aspects, including politics and the economy. At an online meeting between Prime Minister Kishida Fumio and General Secretary Nguyễn Phú Trọng held in February 2023, both leaders agreed to further upgrade the ‘extensive strategic partnership’ between the two countries in this auspicious year.

In the process of preparing for the 50th anniversary, we had a lot of discussions about what has brought about today’s rapid development and intimacy of Japan-Viet Nam relations. The key phrase which emerged in this process is the ‘empathy and resonance’ which is felt by many people involved in Japan-Viet Nam relations.

Of course, the closer relationship between Japan and Viet Nam has been promoted by the overlapping of the political and economic interests of both countries in recent years. However, the rapid development of relations cannot be explained solely in terms of politics and the economy, as we have come to believe there is a unique ’empathy and resonance’ between the two peoples which has been formulated through long cultural and historical exchanges.

In this article, I would like to introduce our views on this special aspect of the Japan and Viet Nam relationship and the background to it, while touching upon the history of Northeast Asia.

The ‘Northeast Asianness’ of Viet Nam

About three years ago, I was posted to Viet Nam as the Ambassador of Japan. At that time, the COVID-19 pandemic had already begun, but the spread of the infection was still under control in Viet Nam, and I was relatively free to walk around the streets of Hanoi and to travel around the country. Therefore, I tried to observe Viet Nam while everything was still fresh, as I had just arrived in Hanoi.

As I had previously served in Indonesia for nearly four years, and had been engaged in various duties related to Southeast Asia at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, I thought I had a certain degree of familiarity with the region. However, after serving in Hanoi for a while, deepening my observations of the Vietnamese people and society, I felt that this country is quite different from other Southeast Asian nations, both historically and culturally. Hence, I started to embrace the following:

‘In order to better understand Viet Nam, I should discard the preconception of the Southeast Asian region. I should rather see Viet Nam in the context of Northeast Asian history.’

About 70% of the vocabulary of the Vietnamese language is derived from Chinese characters. In today’s Viet Nam, the unique alphabet (‘Chữ Quốc Ngữ,’ 字國語) is used exclusively for writing; but Chinese characters were used in official documents until the middle of the 20th century. If you enter the old temples which remain here and there on the streets of Viet Nam, you will find that religious doctrines are written on the plaques (hoành phi, 橫批) and couplets (câu đối, 句對) in Chinese characters.

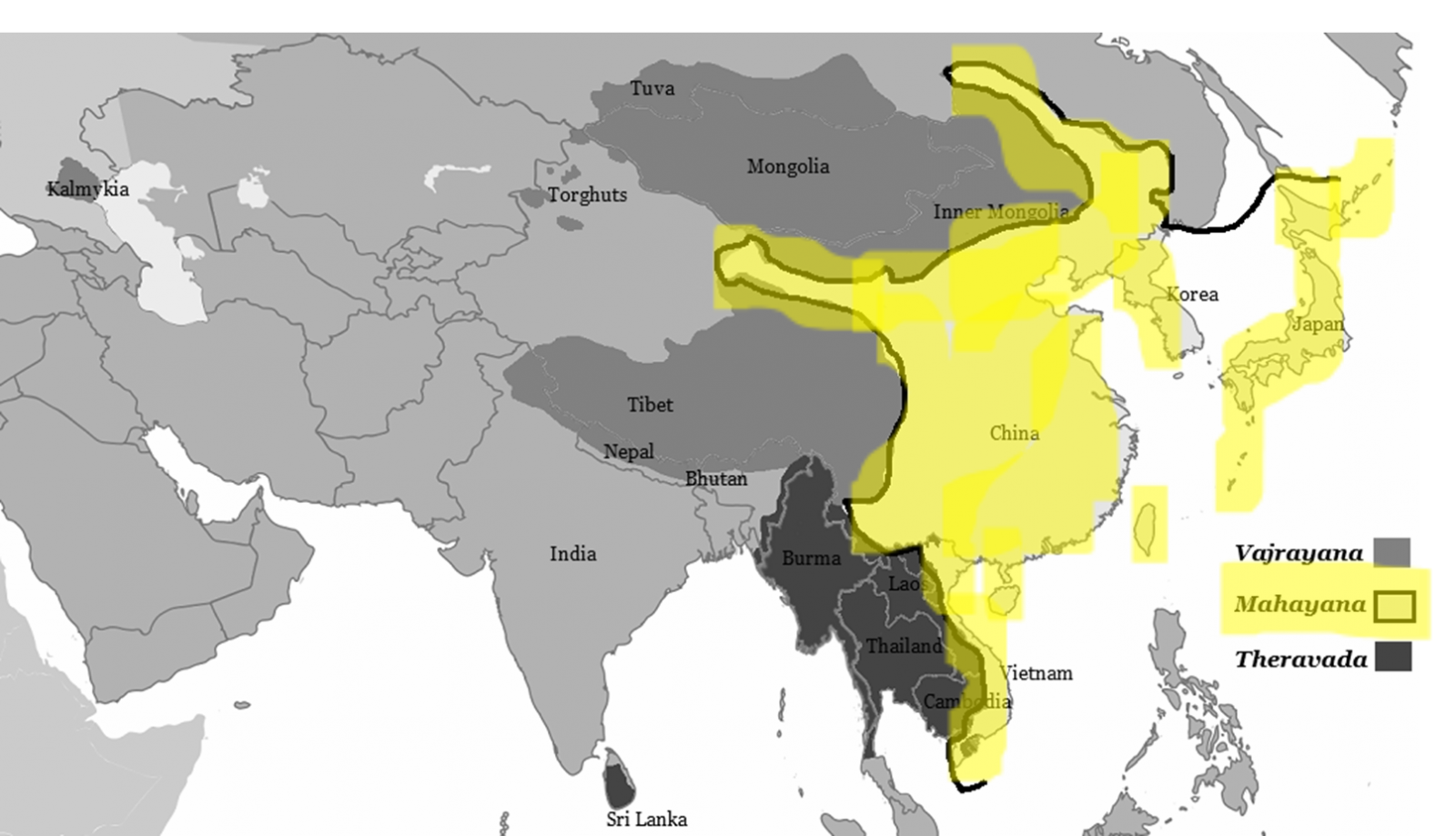

Also, with regard to the state of religion in Viet Nam, while Theravāda Buddhism (Hīnayāna Buddhism) is common in other countries of the Indochina Peninsula, Mahāyāna Buddhism is predominant in Viet Nam, the same as in most parts of Northeast Asia (Fig. 1). Furthermore, the influence of Confucianism has been historically strong in Viet Nam, and the Confucianistic ‘imperial examination’ (khoa cử, 科舉) system continued until the beginning of the 20th century. Even today, Confucian temples (孔子廟) are scattered throughout the country, including the UNESCO World Heritage Site of the Temple of Literature (Văn Miếu, 文廟) in Hanoi.

Figure 1: Expansion of Mahayana

Source: Rupert Gethin, licensed under CC-BY-SA 3.0

The ‘Northeast Asianness’ of Viet Nam was quite a surprise to me, as I came to the country with the preconception of Viet Nam as a Southeast Asian nation. At the same time, this perspective helped me understand Viet Nam’s society and culture. Over the past three years, through my experiences and activities as Ambassador of Japan here, I have come to believe that a unique ‘resonance and empathy’ between the two peoples, which has been nurtured by the ‘Northeast Asianness’ of Viet Nam, has helped the two countries rapidly develop their relations and come closer to each other.

Overview of Vietnamese History

The ‘Northeast Asianness’ of Viet Nam is evident when looking at the history of Viet Nam. After Emperor Hàn Wŭ Dì (Hán Vũ Đế, 漢武帝) attacked Viet Nam in the 2nd century BC, Viet Nam was placed under Chinese rule for more than 1,000 years. In Viet Nam, the period under Chinese domination is called Bắc thuộc (北屬, belonging to the north). It was in the 10th century when the national hero Ngô Quyền (呉權) emerged and defeated the Southern Han army (南漢軍), and recovered the independence of Viet Nam by establishing the Ngô dynasty. During the long period under Chinese rule, the Vietnamese people rebelled many times and maintained their unique social and cultural identity. But it is also true that Viet Nam absorbed a lot of knowledge, customs and skills from Northeast Asia during this period.

There are also records of direct exchanges between Japan and Viet Nam from around the 8th century. A Vietnamese Buddhist monk from Champa called Buttetsu (Phật Triết), together with Bodhisena, a high-ranking priest from the Brāhmaṇa class of Southern India (Bồ Đề Tiên Na), came to Japan via China ruled by the Tang Dynasty. A well-known anecdote is that Buttetsu taught the performance of eight repertoires of the gagaku court dance and music called Rin’yūgaku (Lâm Ấp nhạc, 林邑樂) and consecrated the dance of Karyōbinga (Ca Lăng Tần Già, 迦陵頻伽) to the Buddhābhiṣeka (the eye opening ceremony of the Great Buddha statue) of the Tōdaiji Buddhist Temple in Nara in 752. There is also the story that Fujiwara no Kiyokawa, a Japanese envoy sent to the Tang Dynasty; and Abe no Nakamaro, a Japanese scholar sent to the Tang Dynasty; were shipwrecked on their way back to Japan and washed ashore at Huān-zhōu (Hoan Châu, 驩州), near Nghệ An Province in Viet Nam. It is also well known that Nakamaro was later appointed by the Tang Dynasty as the Zhèn Nán Dū Hù (鎭南都護), the Governor who administered the area of present Hanoi. Around the same time, there was also a story that Heguri no Hironari, a Japanese envoy to the Tang Dynasty, was caught in a storm on his way back to Japan and was adrift until reaching Viet Nam’s Champa (Côn Lôn Quốc, 崑崙國).

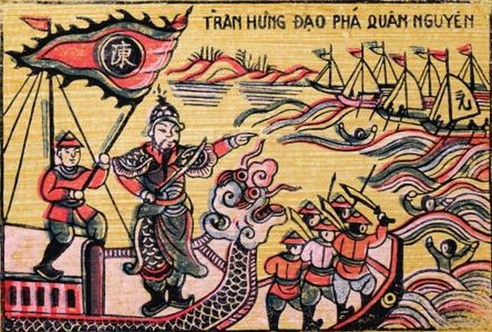

Furthermore, in the 13th century, the Mongol Empire tried to invade Japan twice. Around the same time, Viet Nam’s Trần Dynasty was also attacked three times by the Mongol Empire. During the third Mongol Empire invasion of Viet Nam, General Trần Hưng Đạo (陳興道) inflicted a heavy defeat on the Mongolian fleet in a naval fight the Battle of Bạch Đằng (白藤江之戰) (Fig. 2). It is widely believed that because of this fatal defeat on the Bạch Đằng River, the Mongol Empire gave up its third invasion of Japan.

Figure 2: Battle of Bạch Đằng where General Trần Hưng Đạo defeated the Mongolian fleet (Ðông Hồ painting)

From the 16th century to the 17th century, the red seal ship trade (朱印船貿易[1]) deeply connected Japan and Viet Nam. Viet Nam was the most popular destination for red seal ship trade. It is told that the Tokugawa shogunate’s first Shōgun (tycoon), Tokugawa Ieyasu, loved a fragrant wood (Agarwood) called Kyara (伽羅) or Kỳ Nam (琦楠) produced in Viet Nam. At that time, Hội An (會安), a port city in central Viet Nam, flourished as a commercial hub, and had a large Japanese town with a well-known Japanese bridge (Fig. 3). Porcelain and textiles were brought from Viet Nam to Japan by red seal ships. The love story between a Princess of the Lord of Hội An, Princess Aniō, and a merchant from Nagasaki, Araki Sōtarō, is still remembered in both cities today. An opera performance of this love story, titled Princess Aniō, is scheduled to be presented in both Japan and Viet Nam this autumn as a major commemorative event of the 50th anniversary.

Figure 3: The Japanese Bridge in Hoi An

Figure 4: Lacquer painting of the opera Princess Aniō, designed by Ando Saeko

The ‘Northeast Asianness’ of Viet Nam and Today’s Japan-Viet Nam Relations

I have illustrated above the deep engagement of Viet Nam in the history of Northeast Asia, and I have introduced major anecdotes on the history between Japan and Viet Nam. As I mentioned at the beginning of this article, it may be difficult to understand why Japan-Viet Nam relations have developed so rapidly in recent years unless we recognize the ‘Northeast Asianness’ of Viet Nam, which has been nurtured through long cultural and historical exchanges.

- Why has the number of Vietnamese people living in Japan increased so rapidly in recent years?

(The number of Vietnamese people living in Japan has increased nine-fold in the past 10 years. At the end of 2022, nearly 500,000 Vietnamese people lived in Japan.) - Why do Japanese companies prefer Viet Nam so much as a foreign direct investment (FDI) destination?

(According to a survey by the Japan External Trade Organization (JETRO) conducted last year, Viet Nam is now the most popular FDI destination for major Japanese firms.) - Why is Viet Nam producing a larger number of talented human resources in the field of science and mathematics, including IT engineers, in comparison with other countries in the region?

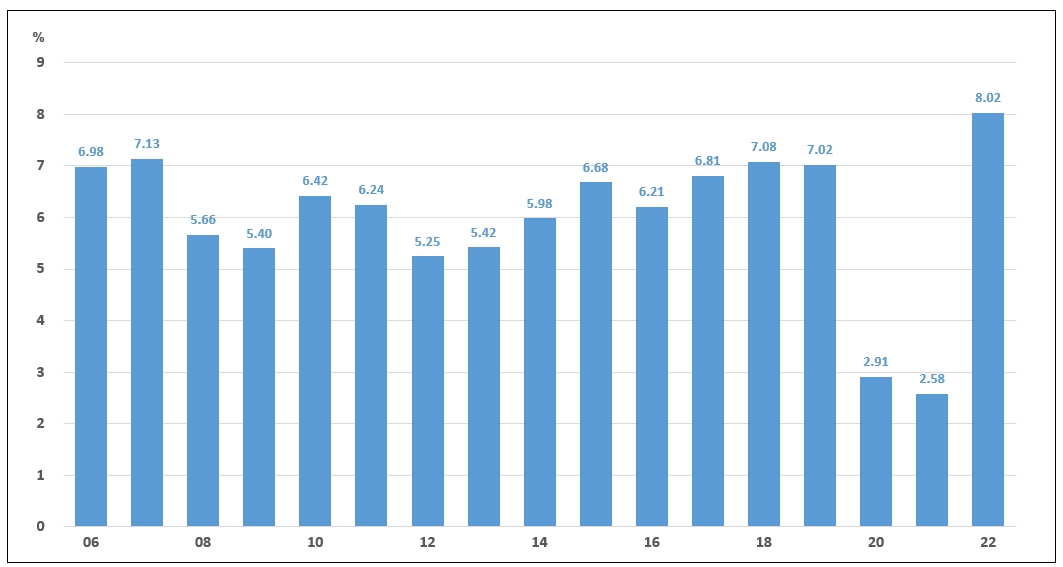

- Why is Viet Nam achieving such rapid economic growth without the major involvement of the ethnic Chinese business community (only with Vietnamese business leaders)? (Fig. 5)

- Why can Vietnamese people learn the Japanese language so quickly, faster than the people of most other countries?

The answers to these questions can partly be found when we consider economics. For example, the rapid increase in the number of Vietnamese residents in Japan in recent years could be partly explained by the wage gap between Japan and Viet Nam. However, there are many countries other than Viet Nam with a similar wage gap with Japan. Hence, it is difficult to explain why the number of people from those other countries living in Japan has not increased so much as Vietnamese people.

We cannot fully understand why Viet Nam and Japan have developed relations so rapidly and have come so close to one another, unless we take into consideration the ‘Northeast Asianness’ of Viet Nam as well as the unique ’empathy and resonance’ between the Vietnamese and Japanese.

Figure 5: GDP growth rate of Viet Nam (annual %)

Source: General Statistics Office of Viet Nam

Viet Nam aims to achieve ‘Northeast Asian standard’ development

Currently, Viet Nam’s per capita GDP is around $4,000. The Vietnamese government has announced its development goals to become an upper middle-income country by 2030 and a developed country by 2045 – the centenary of President Ho Chi Minh’s declaration of independence in 1945.

The announcement of such ambitious goals is a manifestation of Viet Nam’s strong determination to rapidly overcome the middle income trap, which many Southeast Asian countries are still suffering from. In addition, it seems to me that Viet Nam now aims at achieving ‘Northeast Asian standard’ development, similar to that achieved by South Korea and Taiwan, as Viet Nam is now producing a large number of talented human resources in the field of science and technology, who are competitive enough even by Northeast Asian standards.

Needless to say, it is a positive move for Japan that Viet Nam, an important strategic partner in the Indo-Pacific region, sets ambitious goals for her economic development. Japan should provide Viet Nam with as much support as possible.

[1] The red seal ship trade (朱印船貿易) was a type of trade by Japanese sailing vessels mainly bound for Southeast Asian commercial ports with the authorization by the red-sealed letters patent (called ‘Shu-in-jō’). Such letters patent were issued by either Toyotomi Hideyoshi, the most powerful feudal lord of Japan in the late 16th century or by the Tokugawa shōgunate in the early 17th century. Red seal ships were owned and operated mainly by major feudal lords or big merchants of Japan. Between 1600 and 1635, more than 350 Japanese Red Seal ships sailed overseas, and about half of them were bound for today’s Viet Nam.

Viet Nam in ‘Northeast’ Asian History – ‘Resonance and Empathy’ Between Japan and Viet Nam – Vietnam Japan University

ahgtzcregzn

[url=http://www.g63877g94akmp9r4gh19v9sl20vv3o6fs.org/]uhgtzcregzn[/url]

hgtzcregzn http://www.g63877g94akmp9r4gh19v9sl20vv3o6fs.org/